Women in the Prostitution Records

This episode begins by reading an excerpt from a letter that was written on 2 September 1867 by a woman named Anna Andersson who lived in the city of Göteborg. The police had requested Anna to be registered as a prostitute to control the spread of syphilis. Her letter to the police denied it, but the rest of this story is told later in the program.

The episode transitions to describe how people do genealogy. Some researchers try to go as far back in time as possible, and then switch to working on collateral lines. Others focus on learning as much as they can about specific individuals or families. Elisabeth Renström met with Thord Bylund and Kathrine Flyborg at the Härnösand regional archive. Both Thord and Kathrine have spent many years doing genealogy and have even worked at the archive. Here are the tips from Thord and Kathrine to those doing Swedish genealogy:

- Begin by going to living relatives, do interviews to gather the family knowledge

- Verify the family knowledge in records (some information might have been remembered wrong)

- Too often people try to jump to an early generation (which is difficult), start with information that you know. Build from the known to the unknown.

In the last episode of Släktband, they talked about Jonas Berglund who died of syphilis. Sexually transmitted disease, especially syphilis was one of the great problems of society before the 1900’s. To try to control the spread of the disease, the authorities tried to control what they considered was the source, namely women who did not limit their sexual activity to one partner.

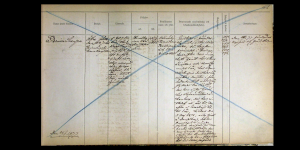

The program transitions, when Elisabeth visits an archive in Göteborg. She interviews Ulf Andersson who works there. They search the Göteborg city police records that were used to register women who were involved in prostitution between 1864 and 1915 (this system was implemented in Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö.) All women who were suspected of prostitution were registered. There were 2 lists, list B was the list for women suspected of prostitution, and list A was for women who were proven to be. The documentation for each woman included: eye color, hair color, shape of nose, and physical build. Files can also include place of residence, names of parents, birthplace, a description of how this woman came to Göteborg, if she has children, if she has contracted sexually transmitted diseases, and where she was confirmed in the Swedish state church. Some of these records have an alphabetical index, but generally people need to search them page by page for the respective time period. There is no comprehensive database, or general index for these records.

Another set of records that a genealogist can check are the medical clinic records (a type of hospital) for disease control. Elisabeth met with Gunnel Karlsson (lecturer with Örebro university in women’s studies) who has researched these records. Gunnel explained that the clinic was society’s way of controlling the spread of sexually transmitted disease. Society at that time believed that prostitution was going to happen regardless, so for the sake of a healthy society, they chose to manage it through city ordinance. The ordinance to control prostitution had requirements that it would not disrupt the mainstream population. It was to be discreet, so other women would not know that it was going on. For example, registered women were not to be out in public before 11:00 pm. Women who were suspected by the police, were summoned to the police office and registered. The women were obligated to go to a medical clinic twice a week for a doctor’s examination. If they had signs or symptoms of a disease, then they were kept at the hospital for treatment (although not curable at the time) and released at a later date. The city ordinance did not monitor or treat the men who had contracted sexually transmitted diseases. In searching the records, Gunnel had found that many of these women left their home parish after their confirmation by moving to the city for employment. But if they became unemployed, then there was no social or economic “safety net” in the city for assistance. Further, in many cases either one or both of their parents were already deceased.

Ulf Andersson and Elisabeth looked at one of the police files and described one woman’s record. She was the daughter of a carpenter in Lödöse who had moved to the city at 18 years old. She worked in mainstream offices, and had other jobs before becoming unemployed a year and a half later. She was registered on list A in April of 1869 before being convicted for vagrancy in 1870 (homelessness was still a crime in Sweden at this time.) She served 2 years in a labor prison. After being released she was convicted again for vagrancy in 1876 and sentenced to 2 more years in a labor prison. In 1878 she is registered again in the police records for prostitution.

Some women who were suspected by the police for prostitution denied it. They could write a letter to the police to be free from registration. A letter might include employment references, referrals to neighbors who can vouch for her staying home at night, and other character references (for example Anna Andersson mentioned at the beginning of the program did this.) But Anna was registered anyway after a man confessed to being with her a few times. Whether money was exchanged or not was not the issue, Anna was registered because she might have contracted a sexually transmitted disease.

Gunnel explains that women were released from registration after they could show employment, an engagement to marry, or if they moved away. Ulf then explained that there are many records to follow a woman forward in time to find out what happened after moving away.

In episode 1 of Släktband they shared the story of Jonas Berglund and his death from syphilis. This episode shared names, dates, and places of women who were registered with the police for prostitution. The question was brought up regarding privacy laws. Ted Rosvall with the Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies (Sveriges Släktforskarförbund) explained that there is really just 1 law in Sweden regarding records and privacy. It’s the 70 year rule that says that records which are younger than 70 years have to be evaluated for sensitivity before being open to the public. Otherwise, the law states that people have a right to see the records, and can generally share the information, except for internet use. If the information is going to be placed on the internet, then special rules apply according to EU regulation. In this case, the EU directives conflict with the Swedish law so a compromise had to be made. The new laws state that if a record is over 100 years old, then it is completely open for use, but what about the time period between 70 and 100 years? The Swedish National Archive was given the responsibility to set appropriate guidelines.

The episode ends with a short interview with Thord an Kathrine to offer suggestions for people doing their genealogy.

What do we learn for Swedish genealogy?

- The police records of registration (List A, and B) that were discussed in this article can be found in Nationell Arkivdatabas under: Göteborgs Poliskammare arkiv, DXIVa, Journaler över prostituerade

- The medical clinic records that were discussed in this article can be found in Nationell Arkivdatabas under: Göteborgs Poliskammare arkiv, DXIVb, Diverse journaler, liggare m.m. angående prostituerade (for Besiktningsjournal)

- The cities that required the registration of prostitution were Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö.

- If you are starting your research, begin by going to living relatives to gather the family knowledge

- Verify the family knowledge in records (some information might have been remembered wrong)

- Too often people try to jump to an early generation (which is difficult), start with information that you know. Build from the known to the unknown.

- Check with other more experienced researchers. They can offer tips and guidance to help you progress faster.

- Many people believe that most genealogical information can be found in databases. Although there are many great databases to help, you cannot complete your genealogy by databases alone.

- The privacy laws for records in Sweden state that records over 100 years old are open to the public. Records that are younger than 70 years old, must be evaluated for sensitive information.

Kriminalpolisen i Malmö DIV:1 (1877) Bild 64 / sid 61

Used by permission from Arkiv Digital at http://www.arkivdigital.net/

Kriminalpolisen i Malmö DIV:1 (1877) Bild 64 / sid 61

Source:

Program: Släktband by Gunilla Nordlund and Elisabeth Renström

Season: 1 – Genealogy Courses and Other Useful Topics

Episode: 2 Kvinnorna i prostitutionsarkiven

Date of publication: 14 November, 2004

Published by: Sveriges Radio P1

Language: Swedish

Link to episode: Släktband 1:2 Kvinnorna i prostitutionarkiven