The Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies (Sveriges Släktforskarförbund) announced 2 fantastic resources will be available through their online bookstore on Nov. 25, 2020. The 1st is the Sweden 2000 Census (Sveriges befolkning). This database will contain everyone who was registered in a Swedish parish at the end of 2000, almost 8.9 million people. Perhaps your wondering how they can publish the 2000 census? It’s because the privacy laws in Sweden are focused on protecting sensitive information and a persons name and address are not deemed sensitive. The 2nd is a new book called Stockholmsforska (in Swedish) that will be focused on the records and strategies for research in Stockholm City. For more information see https://www.rotter.se/senaste-nytt/3409-tva-efterlangtade-nyheter-slapps-snart-i-rotterbokhandeln

Birth and Christening Records for Swedish Genealogy

Are you looking for the birth information of an ancestor in Sweden? The kingdom of Sweden has some of the most comprehensive records for genealogy in the world. Beginning in 1686 every birth and christening was to be recorded by the local parish regardless of religious affiliation. By law all infants were to be christened within 8 days after birth. An emergency christening could be performed if they thought the child might die before getting to the church.

How do you find a birth / christening date?

1. Choose an online provider to access the Swedish church records. The following providers have birth and christening records online:

Arkiv Digital: http://www.arkivdigital.net/ subscription, free access in a FamilySearch Center, images in color, easy navigation

Riksarkivet SVAR: http://sok.riksarkivet.se/ subscription, images in greyscale from microfilm, easy navigation

FamilySearch: https://familysearch.org/ lds account access, images in greyscale from microfilm, less easy navigation

Ancestry: http://www.ancestry.com/ subscription, images in grayscale from microfilm, less easy navigation

2. After you find the online collection for a parish, choose the record type called Födde or Födelse och dopbok (Birth Record.)

3. Browse to the table of contents and find the page number for the births. Navigate to the desired page.

4. Get used to the format and look for key words (see key words list below.)

5. If you know the date, look for the year, month, and date.

6. If you don’t know the date, search each entry looking for the names of the child, or the parents.

What will you find in Swedish birth / christening records?

Should Include:

- Date of birth (depending how the record was kept)

- Date of christening (depending how the record was kept)

- The first and last name of the father

- The first and last name of the mother (depending how the record was kept)

- The parents place of residence at the time of the birth

- The first and last names and residence of the godparents (who may or may not be related to the child)

May Include:

- Entry number

- The name of the woman who held the infant over the baptismal font

- Date of the mothers re-introduction into society (usually about 6 weeks after the birth)

- The mothers age ( beginning about 1750)

- A running total number of males and females born in a given year

Additional Information

- See the Swedish Genealogy Guide video on Swedish Birth and Christening Records (YouTube)

- There was no standard format of how the record was kept until 1894. Sometimes the father’s name is given and the mother’s was left out. You may find the record shows a christening date but no birth date.

- Birth and christenings were generally kept in the same book as the marriages, and burials. Most of the time there is a specific section of a book. Other times the priest kept an ongoing record of all services (births, marriage, deaths) in a chronological order.

- If you do not find the birth entry:

– Check the birth records of the other parishes in the same pastorat.

– Check the parish accounts book. Usually the father paid a fee at the time of the christening. The fee might be recorded in the donations/income record.

- Swedish archive letter for birth records: C

- The dates were usually recorded in the order of: day, month, year

- Sometimes the christening date was recorded according to the religious “feast day” such as Ascensionis Domini (in latin) or Kristi himmelsfärdsdag (Swedish) which converted to May 9 in 1771. If you need to convert a feast day see: Moveable Feast Day Calendar for: Sweden in the FamilySearch Wiki.

Key Words

Here are some common words that are seen in Swedish birth and christening records. The birth entry will also include the marital status of the parents, place names, and maybe the occupation of the father. If the word is not on this list, try to find it in the Swedish Historical Dictionary Database, SHDD

| Swedish | English |

|---|---|

| absolution | receiving forgiveness of sins |

| af | of, from |

| anteckningar | note, annotation |

| barn (barnet) | child, infant (the child) |

| christnades | (was) baptized, christened |

| dag | day |

| den | that, the |

| dess | possessive of den, det |

| dito | ditto |

| Dom., Dominica (latin) | Sunday (the Lord’s day) |

| dop, döpelse, döpt, döptas, döpte, döptes | various uses of the word “dop” = baptism |

| dopbok | baptismal book (record) |

| dopnamn | christian name |

| dop-vittnen | witness to christening |

| ett, en | one |

| fader, far, faderen | father, sire, (the) father |

| fadder, faddrar, faddrarne | various uses of the word ”fadder” = godparent |

| födas, född, födde, föddes, födelse, födt | various uses of the word ”födelse” = birth |

| församling | parish, congregation |

| föräldrar, föräldrarne | parents |

| heta, heter | to be called |

| Hustru, Hu. | Wife, spouse (abbrev. Hu. ) |

| i | in, at, to, upon |

| kalla, kallat | to call, to name, was called |

| kyrkotagning | churching (received to the parish) |

| kön (man-, qvin-) | sex, gender (male, female) |

| med | with |

| moder, moderen | mother, (the) mother |

| månad | month |

| namn, namnet | name, (the) name |

| nöd-döpt | baptism in case of necessity, or emergency |

| och, ock | and |

| oäkta barn | Illegitimate child, bastard child |

| piga, pigan, pig. | maid, maidservant (abbrev. Pig.) |

| stånd | state, class, rank |

| susceptrix (latin) | person who held the infant over the baptismal font |

| testes (latin) | witness |

| uti | see i |

| vittne, vittnen | witness, (the) witness |

| år, åhr | year |

Vaccinations in Sweden

Variolation or inoculation against smallpox began as early as 1756 in Sweden. The technique was to rub powder from smallpox scabs or fluid from pustules into small cuts to create a controlled exposure to the disease. The hope was that a person’s immune system would develop resistance through small exposure.

Dr. Edward Jenner (of England) published his analysis of smallpox vaccination in 1798. By 1800 Jenner’s work had been translated into Swedish and Dr. E. S. Munck af Rosenschöld practiced the technique in Lund in 1801. Vaccination against small pox was quickly recognized as an effective practice to prevent epidemics of the disease. By 1810 the practice of small pox vaccination was wide spread in Sweden and was performed by doctors, priests, and church wardens. Because the church assisted with vaccinations, you may find vaccination records in the ministerial book, household examinations, or in a book of its own. Beginning in 1816 all children in Sweden had to be vaccinated for smallpox by law. The disease still had outbreaks in the 1800’s in Sweden but effected mostly elderly people who had never been vaccinated. The public requirement for smallpox vaccination in Sweden was discontinued in 1976.

Source: Nordisk familjebok. Uggleupplagen 2, ”Vaccination”, Stockholm 1921, page 205

Image from ArkivDigital, Tuna (C), C:3 (1716 – 1766) bild 214/sid 454

Torps in Sweden

In the middle of the 1800’s there were about 100, 000 torps (small farms) in Sweden with roughly 500,000 people living on them. At that time there were about 3.5 million people in Sweden, so about one seventh of the population was living on torps.

Torps in mid- and southern Sweden were usually leased from a larger farm. Torps in northern Sweden were often owned (as there was no large scale farming in the north.) Either way the torps generally did not have the best plots of land for farming. Sometimes they were used to break a new section of ground for farming next to a large farm, or from government owned land such as the Kronotorps in northern Sweden.

The Renting Torpare

If the Torpare (farmer who ran one of these small farms) rented the torp from a larger farm, then there was no property tax on the torp. The property or production taxes were associated to the larger farm. Rent for the torp could have been paid in goods or labor such as the day labor torp (dagsverkstorp.) Other terms for this kind of torp were Jordtorp or Stattorp. The day labor torps were abolished in 1943 when the Stattare system was dismantled.

Förpantningstorp meant it was a torp with possession rights for generally 49 years. As part of the contract the Torpare made a payment at the beginning in exchange for fewer obligations in day labor. Another type of torp was the undantagstorp which was in consequence to an inheritance or sale.

The Soldier Farm

Maybe you have heard of soldier farms? This was another form of torp. You might see the title Soldattorp, Ryttartorp, Båtmanstorp, or even Knekttorp in the records. These were small farms used for the soldiers of the Allotment System starting in the 1680’s. Primarily these farms provided residence for the soldier / or sailor (in the navy) and their family. The farm was too small to be self-sustaining so the local farmers with large farms were obligated to provide agricultural products and use of draft animals. In some parts of Sweden the soldier farm was given to the soldier at the end of military service. More commonly, the soldier and his family had to move after the discharge (or death) of the soldier.

Torps in the 1900’s

In the late 1800’s there was a massive emigration from Sweden, plus migration to the cities due to the industrial revolution, and the practice of the military Allotment System and its soldier farms was discontinued. With so much change in society, many of the torps were converted into summer cottages in the early 1900’s. Other summer cottages were built in the early 1900’s as the population grew. The newer cottages were given newer names, while many of the older torps were re-named by new owners to dis-associate from the social stigmas of the old torps. This re-naming can be one reason why you have a hard time finding the location of an older torp on a modern map. Gratefully there is an abundance of historic maps for Sweden. You can use historic maps to find the location of an older torp and then try to find the same place on a modern map.

Source: Börja forska kring ditt hus och din bygd by Per Clemensson and Kjell Andersson, Natur & Kultur, Stockholm, 2011 pages 80 – 90.

You can learn more about historic maps of Sweden at: https://familysearch.org/learn/wiki/en/Historical_Maps_of_Sweden

Photo by GFröbergMorris, Soldiers cottage at Skansen outdoor cultural history museum, Stockholm 2008.

Types of Farms in Swedish Records

While reading Börja forska kring ditt hus och din bygd, I learned some interesting things about farms in Sweden. In the middle of the 1700’s there were about 187,000 farms in Sweden. By 1870 there were 234,000. On every farm you had the family who owned or leased the farm along with servants (usually from the younger working class who probably came from nearby.) Often the farms had smaller leased torps or backstugor associated to them.

Each farm had a ownership status ranked in a system called “jordnatur”. There were 3 types of farms within jordnatur:

Skattegård – were independently owned farms. The owner paid taxes directly to the government.

Kronogård – were owned by the government and leased to the farmer.

Frälsegård – were owned by the nobility and leased to the farmer.

In 1700 each group was about the same size, 1/3 Skatte, 1/3 Krono, and 1/3 Frälsegård. Over time the government sold Kronogårds to independent farmers using transactions called Skatteköp. This continued so by the late 1800’s about 60% of the farms were Skattegård. At that time the Frälsegård still made up about 1/3 of the farms especially in Mälardalen, Östergötland, and Skåne.

Knowing this helps to understand the social standing of your Swedish ancestors. The household examinations show the occupation of the head of household. If your ancestor was listed as a Skattegårdsman (or Skattebonde), the farm was privately owned. The Kronogårdsman (or Kronobonde) had a lease to a government owned farm, and the Frälsegårdsman (or Frälsebonde) had a lease to a farm owned by the nobility.

Source: Börja forska kring ditt hus och din bygd, by Per Clemmensson and Kjell Andersson.

Picture: from Skogaholm manor at Skansen in Stockholm, taken by GFröbergMorris in 2008

Swedish Genealogy in Cities

Chances are at some point you will find a Swedish ancestor that lived in a city. You’ll find that genealogical research in cities is different than in rural areas. The parish was still responsible to keep the vital records of birth, marriage, and death, but there are unique differences due to city life. This article will help you understand those differences and offer some resources to find your ancestors in the cities.

Historically the largest cities in Sweden have been Stockholm, Göteborg, Malmö, and Norrköping. When you rank the cities by size, you’ll find the order of largest to smallest varies according to time period. Stockholm was the largest city beginning in the late 1500’s and has been ever since. Before 1850 Stockholm and Göteborg were the only cities with a population over 20,000. Between 1850 and 1930 the population of Stockholm increased to 500,000, and Göteborg to about 250,000. In the same time period Malmö breaks 100,000 and Norrköping hits about 70,000.

Life in the Cities

Life in cities is built upon manufacture, distribution, and trade. In Sweden the government controlled the privileges of a town or city to participate in these activities. All the larger cities were ports for trade. These cities also had a stronger military presence.

The cities had a wider diversity of people from other countries. These people brought other languages, traditions, naming customs, and religions. Although Sweden had the Lutheran state church, they allowed other groups of people to practice their respective faith. As the natural resources and opportunities vary by location, you find that towns and cities became known for certain products.

Challenges of Research in Cities

There are many challenges to finding your ancestor in the cities. Here are some of the big ones:

Population Size

Simply put, the larger the community.. the harder to find the person that you’re looking for. Sometimes in the larger cities, it can feel like searching for a needle in a haystack.

Migration

Every city started out as a small village. Over time people moved to the cities for opportunities. Once in a city, a person might move for a better job or better housing. Workers in cities were not tied to the land. There was job stability and in-stability. Many workers had to renew an annual contract. Relocation was common, and just like today having connections was important. All these situations lead to the questions of “where did this person come from?” or “where did they go to?”

The Church in the Cities

A priest in the Swedish Lutheran church was responsible for keeping birth, marriage, and death records for all the people that lived within their parish boundary. These are called Territorial parishes because they have a geographic boundary. In the larger cities, there are congregations that gather for other reasons such as language, or the military. These parishes are called Non-territorial parishes because there isn’t a geographic boundary within the city. In most cases there is a city parish (Stadsförsamling) for people who lived in the city, and a rural parish (Landsförsamling) for the people who lived near the city.

Because there were so many people to keep track of, the parish priest and his staff struggled to keep accurate household examination and moving records. As the population increased and the number of members within a parish increased, the diocese would split the older parish to create a new parish. Statistically there were higher rates of illegitimate births in the cities. This was especially true between 1778 and 1917 when a mother could give birth anonymously. Residency in the records is listed by Rote (like a neighborhood), streets, or even households within a building.

Naming customs

After moving to the city, many people changed their surname for practical reasons. There were too many people with similar names. To change a surname was easy, just start using it. Over time your new surname would become what you’re known by with your friends, family, employer, on the church records, and with tax authorities. The challenge is finding what the patronymic surname was before moving to the city. Also, there was a wider variety of given names in the cities, many of which came from other countries.

Orphanages

There were many situations that led a child to the orphanage. It could be the death of parents, a single parent unable to provide for a child, or a temporary situation of failing health, or imprisonment. Whatever the case, children were taken to orphanages for care. All cities were required to have an orphanage according to the law of 1624. There were public and private orphanages. See the article Orphanages in Sweden on the FamilySearch Wiki.

Military

The larger cities had an increased military presence made up of professionals, and non-professionals in the army or navy. They lived in military quarters and belonged to military church congregations. The question is “where did they come from” and after their service “where did they go to?”

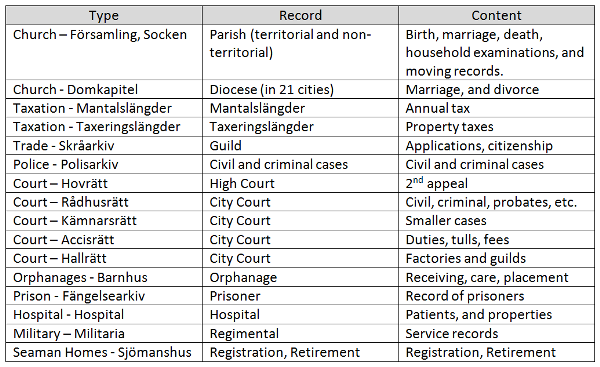

Records in Cities

There are many records available to search for your ancestor in a Swedish city. Here is a short list:

Here are some resources for genealogical research in Swedish Cities:

Stockholm

- Tidigmoderna konkurser 1687 – 1849, see Tidigmoderna konkurser databas

- Mantalslängder 1760 (Stockholm City Archive)

- Mantalslängder 1810 (Stockholm City Archive)

- Mantalsuppgifter 1835, 1845, 1860, and 1870 (Stockholm City Archive)

- Mantalsregister 1800-1884 (Stockholm City Archive)

- Indexes for parishes in PDF, through Stockholm Stadsarkiv website at: Kyrkoarkiv

- 1878-1926 Roteman database (Stockholm City Archive), also available for purchase on DVD through Sveriges Släktforskarförbund.

- 1926-1939 Överståthållarämbetet, available through Arkiv Digital.

- For orphanages see the article: Orphanages in Sweden on the FamilySearch Wiki.

Göteborg

- Index of Marriages for Kristine parish 1624 – 1774, FHL Intl book 948.69/G1 H2b v.3

- Rådhusrätt register 1719 – 1798, FHL microfilm Intl 216069 – 216070

- Göteborg tomtägare 1637 – 1807 at: Göteborgs tomtägare 1637 – 1807

Malmö

Norrköping

- Tax records index for all tax obligated 1727-1945 at the Norrsköping Stadsarkiv. Contact the archive for assistance.

Resources for Other Cities

1. PLF (Person-och Lokalhistoriskt Forskarcentrum) on CD for all cities in Småland (Jönköping, Kalmar, and Kronoberg Counties.) These include: Borgholm, Eksjö, Gränna, Huskvarna, Jönköping, Kalmar, Oskarshamn, Vimmerby, Västervik, and Växjö

2. Demografisk Databas Södra Sverige (DDSS) for Skåne (Malmöhus, Kristianstad), Blekinge, and Halland Counties. These include entries from birth, marriage, and death records of: Båstad, Helsingborg, Höganäs, Karlskrona, Kristianopel, Kristianstad, Malmö, Ronneby, Vä, Ystad, Åhus, and Ängelholm. Within DDSS there is the Halland Marriage Database that will help for the cities of Falkenberg, Halmstad, Kungsbacka, Laholm, and Varberg.

3. Indiko (Demografiska databasen Umeå universitet) for Linköping, Skellefteå, and Sundsvall.

4. Födda, Vigda, Döda i Ådalen, CD available at FHL or can be purchased through Riksarkivet for Härnösand and Sollefteå.

5. Register of births, marriages, and deaths in Jämtland 1642-1860 on FamilySearch.org, 1686-1875 on microfilm INTL 1644180 for Östersund.

DDSS Website for Swedish Genealogy

Background of DDSS

The DDSS database was started in 1996 by the staff at the Regional Archive of Lund. It is a product of 3 databases called the Demographic Database of Southern Sweden (DDSS), the Skåne Demographic Database (SDD), and the Malmö City Archive Birth Register Database. The goal is to create one database that has all the birth, marriage, and death information (up to 1894) for the parishes within the geographical area that the archive is responsible for. The regional archive of Lund has responsibility for the counties of Skåne (Malmöhus 1669-1997, and Kristianstad 1719-1997), Blekinge, and Halland. Although Halland belongs to the area jurisdiction of the regional archive of Lund, the data for Halland is being registered into the Svensk Lokalhistorisk Databas.

The DDSS database was created by volunteers (many of which are unemployed or unable to get employment), genealogists, and the staff at the regional archive of Lund. Because the data is also for academic use, every entry is reviewed by an experienced genealogist. Although this ongoing project has had economic challenges at times, the database has continued to grow. As of April 30, 2014 the database has over 1.5 million searchable entries from about 400 parishes. Over 23.6 million visitors have visited the website since 2003.

About the DDSS Website

The DDSS website offers many useful and interesting databases. The largest database is the Demographical Database for Southern Sweden. It has:

- A birth and christening database which includes data from the DDSS, Malmö City Archive Birth and Christening Database, and the Skåne Demographical Database (SDD.)

- An engagement and marriage database which includes data from the DDSS and SDD.

- A death and burial database which includes data from the DDSS and SDD.

- A migration database that is created from the parish moving-in and -out records of 9 parishes. This data came from the SDD.

The DDSS website allows you to search data from the three sources (DDSS, Malmö City Archive, SDD) at the same time. There are some restrictions to the data which are:

- No birth or christening entries are listed that are younger than 100 years

- No engagement or marriage entries are listed that are younger than 70 years

- No death or burial entries are listed that are younger than 70 years

- No causes of death are listed that are younger than 100 years

Other features include:

- First names, last names, titles, place names, and causes of death can be searched using a standard or non-standard spelling. If you want to search using a non-standard spelling type a quotations mark (“) before the word. The DDSS website offers a good page of search tips, see DDSS Search help.

- One of the great search tools is the wildcard. You can use the asterisk symbol (*) to replace one or more characters of a word. It can even be used multiple times in the same word.

- There are 2 ways you can find what parishes are included in the database. 1. You can click on the county that is shown on the DDSS home page. Then click on the Härad or City on the next map, and then browse down the list of parishes. 2. You can click on Databases, choose a birth, marriage, or death database and then use the drop down menu to see if a specific parish in included.

- The registration for a parish always begins with the records of the late 1800’s, and then progressively works back earlier in time. The earliest parish records are done last.

- You’ll find there is some inconsistency to the extracted data, for example some birth entries include godparents and others do not. This is because the birth data has been contributed by multiple organizations that had different rules in the extraction process.

The website also offers:

- A database which includes most of the marriages in the county of Halland, called the Vigselregister Halland which is available on the DDSS website. This database was created by the Hallands Släktforskarförening (Hallands Genealogical Society.)

- A database called Sveriges Skepplistor, which is a database of Swedish ships between the years of 1837 and 1885. The data is from published ships lists that are in the Regional Archive of Lund.

- The Karlskrona Sjömanshusdatabas (Karlskrona Seaman’s Home) is a collaborative effort by ArkiVara in Karlskrona, the Municipality of Karlskrona, and the Regional Archive in Lund. They are extracting the registration records from the Karlskrona Seaman’s Home between the years of 1871 and 1937. This pertains to all seamen who registered and donated money to their future care, and retirement.

- The Öknamnen i Örkened database (Nicknames in Örkened) which is a database built upon the nicknames that were associated to the people and place names in Örkened parish in Skåne County. Historically many people had nicknames in their local parish. The goal of this database is to register the different nicknames used in Örkened parish, discover their origin, and associate these names to the people and places they belonged to.

- A transcription copy of the ministerial book of Osby parish (C:1) from 1697 – 1690 in PDF.

Another option on the DDSS website is the Temasidor (Theme pages.) This part of the database offers tools, and presentations (in Swedish) on various subjects including:

- Given names in a historical context

- Last names in a historical context

- A list of place names in Skåne and Blekinge

- Occupations and Titles

- Demographic Statistics

Use for Swedish Genealogy?

- Search for birth, marriage, or death information for about 400 parishes in Skåne (Malmöhus and Kristianstad), and Blekinge Counties.

- The DDSS is especially useful in the cities where there are parishes without a specific geographical boundary (non-territorial parishes.)

- Search for migration information from 9 parishes in Skåne.

- Search for a marriages in Halland County.

- Search place names of the villages and farms in Skåne and Blekinge Counties.

- See maps of the Härads in Skåne and Blekinge Counties.

- A transcription copy of the Osby ministerial book from 1647 – 1690.

Database Information

Swedish Name: Demografisk Databas Södra Sverige, DDSS

English Name: Demographical Database for Southern Sweden

Purpose: To create a database of birth, marriage, and death information for all the parishes in Skåne (Malmöhus, Kristianstad), Blekinge, and Halland. It was created for genealogists, local historians, educators, historical societies, academic research in demography, and medical research.

Created by: The Regional Archive of Lund (Landsarkivet i Lund)

Format: Online at http://www.ddss.nu/

Cost: Free

Language: Swedish, English

Sources:

- The Demografisk Databas Södra Sverige (DDSS) website

- Haskå, Guno. Släkthistorisk Forum: Person- och lokalhistoria i undervisningen. Sveriges Släkforskarförbund, no. 2, 2004

Släktband Review, Season 1 Episode 3

Family Secrets

This episode begins with a man named Kjell Weber of Torslanda who shared 2 family secrets. One was a family story that had been passed down for generations. The story goes that the family name of Ödman went back to an English seaman whose last name was Smith. He was shipwrecked and came ashore to an island called Skaftö which is off the coast of Bohuslän by floating on a plank. Then he found an abandoned house (Ödehus) where he settled down and stayed. Smith eventually changed his last name to Ödman as a variation on the name of the house. Kjell found that an early generation had sons that simply took the name Ödman to replace their patronymic names. When Kjell shared this with his family, an Aunt was not happy to hear the truth. Elisabeth Renström summarized that this story had been passed down for generations, but it turned out to be just a story. The English seaman whose name was Smith had never existed and some of the modern family was not happy to hear the truth.

The episode transitions to another interesting topic, the naming patterns of given names in Sweden. Elisabeth Renström met with Margareta Svahn, a manager with the Dialect, Place Name, and Cultural Archive (Dialekt ortnamns och folkminnesarkivet) in Göteborg. Magareta shared some interesting points regarding “given names” such as:

- In rural areas many people named their children according to “traditional given names” in the family. For example, they might name the first son after the father’s father and the first daughter after the mother’s mother.

- You’ll see that some given names were popular in an area, such as many parents naming their sons Per, Anders, or Karl in a village.

- By the 1700’s and 1800’s people started to use given names from other countries. Naming practices changed first in the cities, and then eventually in rural areas.

- The first group in society to use foreign given names was the townsman, or citizen social class (the Borgare.)

- Some illegitimate children were given unusual first names because 1. The unwed mother may have been employed as a household servant by the borgare (she was influenced by non-traditional names) and 2. Having a child out of wedlock had a negative social stigma so the mother might break from family traditions.

- A child’s given name might have been influenced by the priest. There are examples where the priest was told by the parents what the name should be (even written on paper), but the priest didn’t like it so he chose something else.

- The priest might have christened the child according to a proper form of the name. For example, the parents requested Kajsa but he recorded the name as Karen or Katarina. The child’s name is recorded in the birth record as Karen or Katarina but she was known throughout her life as Kajsa.

- Although a child’s name was recorded in the birth record with one spelling, it doesn’t mean that anyone kept using that spelling in other records.

- During Viking and early Medieval times people used Nordic names (such Asmund, Ingrid, and Sven.) Christianity brought a variety of given names, especially from the liturgical calendar such as Andreas, Johannes, Petrus that became Anders, Johan, and Per.

- The time of Sweden’s wars and expansion in the 1600’s brought names from other countries especially France and Germany. Names from other countries become popular in the 1700’s (first in the larger cities) and then in the 1800’s throughout the rest of the country.

The episode switches to the topic of a project called Namn åt de döda 1950 – 2003 (meaning Names of the dead) that was led by the Swedish Federation of Genealogical Societies (Sverige Släktforskarförbund.) The information from this project was published on a C.D. database called Sveriges Dödbok (maning Swedish Death Book), which has multiple versions (latest is 1901 – 2009 that has about 7.1 million people in it.) The database includes other information such as birthdate, their personal i. d. number (if the person died after 1947), social standing, birth parish, and the residence parish at the time of death. The purpose of the database is to help people find information about when someone died without having to visit a regional archive or contact a parish. The legal responsibility for parishes to keep vital records stopped in 1991.)

Elisabeth Renström switches back to her interview with Kjell Weber who shared another piece of the family story, this time an ancestor guilty of murder. The ancestors name is Karl Johansson who was a guard at the city jail in Göteborg. One evening in the spring of 1847 Karl and a friend went out for a walk. They went down a darkened street where they ran into 3 other men, one of them being in the military. The men began to mock and insult each other, all of the men participated but it was mostly between the military man and Karl. Court documents do not show what the insults were about, but the insults turned into a fight. The story goes that suddenly Karl breaks into an insane rage; he picked up a wooden shovel that happened to be nearby and began to beat one of the 3 men who was the slowest.

Karl beat the youngest of the group, a young man named Daniel Jacobsson who worked in one of the cigar factories to death. One of the witnesses who testified in court, was a laborer named Andreas Kristensson. He described how Karl came out from a doorway with the shovel in hand to chase the young man. The city court records show that another witness described the yelling, and sounds of the blows. It was dark and somewhat unclear who actually did the beating, but another witness said it was Karl.

Karl was convicted for murder and condemned to the death by beheading. The conviction was appealed to an appellate court, but the conviction was upheld. It was appealed again to the Swedish Supreme Court with a request for mercy from the King. The King upheld the conviction but the penalty was changed to 28 days on bread and water (which was equivalent to a death sentence), public confession, and 10 years at a labor prison. Karl served his time at the labor prison in Malmö between 1848 and 1858. After his release, Karl returned to Bohuslän where he found work as a laborer, eventually married and had a family.

Kjell shared the story of the English seaman, and other stories that had been passed down to illustrate how family’s keep secrets, and other things are only partially true.

The episode ends with some research advice from Thord Bylund and Kathrine Flyborg:

– You start with building your family tree as far back as you can.

– Eventually you can’t go further back, so you work on collateral lines or pick an early ancestor and work your way down the descendants.

– The research in the 1800’s is usually the easiest to work in.

– Another research activity is to gather family photos, and then collaborate with extended family to identify the people in the photos.

What do we learn for Swedish genealogy?

- Some family stories are simply wrong, and some family members will not be happy to hear the truth.

- There is a rich and interesting history to the given names in the Swedish culture.

- The records in Sweden are very good. As you search the records you will find family secrets, or discover the truth of a family story.

Source: Släktband by Gunilla Nordlund and Elisabeth Renström

Season: 1 – Genealogy Courses and Other Useful Topics

Episode: 3 Släkthemligheter

Date of publication: 21 November, 2004

Published by: Sveriges Radio P1

Language: Swedish

Link to episode: Släktband 1:3 Släkthemligheter

Type Swedish Letters Å, Ä, and Ö for Genealogy

The Swedish alphabet has 29 letters, A through Z plus Å, Ä, and Ö. Sometimes you will see other letters with marks above them such as é, á, ü, or ÿ, but these letters are considered variants of e, a, u, and y. Because the letters å, ä, and ö are letters in the Swedish alphabet, you should use them in your genealogical data entry, searching for Swedish genealogical websites, or using databases from Sweden. Here are some examples in correct spelling:

First Names:

Ake is Åke

Goran is Göran

Hakan is Håkan

Jons is Jöns

Par is Pär

Last Names:

Aberg is Åberg

Akerberg is Åkerberg

Backman is Bäckman

Oman is Öman

Ostman is Östman

Soderberg is Söderberg

Wahlstrom is Wahlström

Place Names:

Akarpsgarden is Åkarpsgården

Algsjon is Älgsjön

Ostergarden is Östergården

Sodra Fagelas is Södra Fågelås

Vasteraker is Västeråker

Here are some options to type the letters Å, Ä, and Ö on a English keyboard:

Use the 10 keypad in Windows

Hold down the Alt key and type one of codes below into the 10 keypad. When you let go of the Alt key, the letter will appear.

Å is 143

å is 134

Ä is 142

ä is 132

Ö is 153

ö is 148

MAC

To get the umlaut above a letter:

1. Hold down the Option key, and type u (the letter u).

2. Let go of the keys (don’t hold them down for step 3).

3. Type the vowel over which you want the umlaut to appear.

Hold the Shift key down in step 3 Above.

Option+A = å

Shift+Option+A = Å

Option + u, then a = ä

Option + u, then shift + A = Ä

Option + u, then o = ö

Option + u, then shift + O = Ö

Copy and Paste from a Swedish Website (Windows)

1. Find a Swedish website

2. Highlight a letter using the mouse, then with the mouse pointer on the highlighted text, do a right click on the mouse and choose copy (or hold down the Ctrl key and press the letter c).

3. Move the mouse pointer to the place want to paste. Click one time so the curser is active. Right click on the mouse and choose paste (or hold down the Crtl key and press the letter v).

Keyboard Settings (Windows)

Another option is to change the language input for your keyboard in Windows. In this method, you use the Control Panel to activate the Swedish keyboard. After the keyboard is activated you should see an icon in the lower right corner of your screen that looks like EN. Click on the EN to see a list with the option of choosing English or Swedish. Choose Swedish. The EN should have changed to SV.

As long as the icon is SV, you are using the Swedish keyboard. While in the Swedish keyboard mode the Å, Ä, and Ö can be used on your English keyboard as follows:

• Ä is the ‘ (or “ ) key

• Å is the [ (or { ) key

• Ö is the ; (or : ) key

For the upper case or lower case of each letter, use the Shift key as usual. While the Swedish keyboard is active, some keys on your English keyboard are rearranged too (especially on the number keys across the top.)

Here are instructions to change the language keyboard in Windows. Choose the operating system below:

Windows 8

1) Swipe (or move your mouse pointer) to the lower right corner of the screen and click on Settings

2) Change PC Settings

3) Tap or click on Time and language

4) Tap or click on Region and language

5) Tap or click on Swedish and then on Options

6) Tap or click Add a keyboard

7) Browse to the input method to keyboard, and click it

Windows 7

1) Click on the Windows symbol in the lower left corner of the screen

2) Control Panel

3) Look for Clock, Language, and Region. Click on the small link below the title that says Change keyboards or input methods

4) Change keyboards…

5) Leave it on the General tab and click on Add

6) Scroll down and click on the + symbol next to Swedish

7) Then click on the + symbol next to the word keyboard

8) Then click in the little empty box next to Swedish. This should create a check mark in the box.

9) Click on OK, Apply, OK, OK

10) Close the Control Panel box

Windows Vista

1) Click on the Windows symbol in the lower left corner of the screen

2) Control Panel

3) Regional and Language Options

4) Click on the Keyboards and Languages tab

5) Change keyboards…

6) Leave it on the General tab and click on Add…

7) Scroll down and click on the + symbol next to Swedish

8) Then click on the + symbol next to the word keyboard

9) Then click in the little empty box next to Swedish. This should create a check mark in the box.

10) Click on OK, Apply, OK, OK

11) Close the Control Panel box

Släktband Review, Season 1 Episode 2

Women in the Prostitution Records

This episode begins by reading an excerpt from a letter that was written on 2 September 1867 by a woman named Anna Andersson who lived in the city of Göteborg. The police had requested Anna to be registered as a prostitute to control the spread of syphilis. Her letter to the police denied it, but the rest of this story is told later in the program.

The episode transitions to describe how people do genealogy. Some researchers try to go as far back in time as possible, and then switch to working on collateral lines. Others focus on learning as much as they can about specific individuals or families. Elisabeth Renström met with Thord Bylund and Kathrine Flyborg at the Härnösand regional archive. Both Thord and Kathrine have spent many years doing genealogy and have even worked at the archive. Here are the tips from Thord and Kathrine to those doing Swedish genealogy:

- Begin by going to living relatives, do interviews to gather the family knowledge

- Verify the family knowledge in records (some information might have been remembered wrong)

- Too often people try to jump to an early generation (which is difficult), start with information that you know. Build from the known to the unknown.

In the last episode of Släktband, they talked about Jonas Berglund who died of syphilis. Sexually transmitted disease, especially syphilis was one of the great problems of society before the 1900’s. To try to control the spread of the disease, the authorities tried to control what they considered was the source, namely women who did not limit their sexual activity to one partner.

The program transitions, when Elisabeth visits an archive in Göteborg. She interviews Ulf Andersson who works there. They search the Göteborg city police records that were used to register women who were involved in prostitution between 1864 and 1915 (this system was implemented in Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö.) All women who were suspected of prostitution were registered. There were 2 lists, list B was the list for women suspected of prostitution, and list A was for women who were proven to be. The documentation for each woman included: eye color, hair color, shape of nose, and physical build. Files can also include place of residence, names of parents, birthplace, a description of how this woman came to Göteborg, if she has children, if she has contracted sexually transmitted diseases, and where she was confirmed in the Swedish state church. Some of these records have an alphabetical index, but generally people need to search them page by page for the respective time period. There is no comprehensive database, or general index for these records.

Another set of records that a genealogist can check are the medical clinic records (a type of hospital) for disease control. Elisabeth met with Gunnel Karlsson (lecturer with Örebro university in women’s studies) who has researched these records. Gunnel explained that the clinic was society’s way of controlling the spread of sexually transmitted disease. Society at that time believed that prostitution was going to happen regardless, so for the sake of a healthy society, they chose to manage it through city ordinance. The ordinance to control prostitution had requirements that it would not disrupt the mainstream population. It was to be discreet, so other women would not know that it was going on. For example, registered women were not to be out in public before 11:00 pm. Women who were suspected by the police, were summoned to the police office and registered. The women were obligated to go to a medical clinic twice a week for a doctor’s examination. If they had signs or symptoms of a disease, then they were kept at the hospital for treatment (although not curable at the time) and released at a later date. The city ordinance did not monitor or treat the men who had contracted sexually transmitted diseases. In searching the records, Gunnel had found that many of these women left their home parish after their confirmation by moving to the city for employment. But if they became unemployed, then there was no social or economic “safety net” in the city for assistance. Further, in many cases either one or both of their parents were already deceased.

Ulf Andersson and Elisabeth looked at one of the police files and described one woman’s record. She was the daughter of a carpenter in Lödöse who had moved to the city at 18 years old. She worked in mainstream offices, and had other jobs before becoming unemployed a year and a half later. She was registered on list A in April of 1869 before being convicted for vagrancy in 1870 (homelessness was still a crime in Sweden at this time.) She served 2 years in a labor prison. After being released she was convicted again for vagrancy in 1876 and sentenced to 2 more years in a labor prison. In 1878 she is registered again in the police records for prostitution.

Some women who were suspected by the police for prostitution denied it. They could write a letter to the police to be free from registration. A letter might include employment references, referrals to neighbors who can vouch for her staying home at night, and other character references (for example Anna Andersson mentioned at the beginning of the program did this.) But Anna was registered anyway after a man confessed to being with her a few times. Whether money was exchanged or not was not the issue, Anna was registered because she might have contracted a sexually transmitted disease.

Gunnel explains that women were released from registration after they could show employment, an engagement to marry, or if they moved away. Ulf then explained that there are many records to follow a woman forward in time to find out what happened after moving away.

In episode 1 of Släktband they shared the story of Jonas Berglund and his death from syphilis. This episode shared names, dates, and places of women who were registered with the police for prostitution. The question was brought up regarding privacy laws. Ted Rosvall with the Federation of Swedish Genealogical Societies (Sveriges Släktforskarförbund) explained that there is really just 1 law in Sweden regarding records and privacy. It’s the 70 year rule that says that records which are younger than 70 years have to be evaluated for sensitivity before being open to the public. Otherwise, the law states that people have a right to see the records, and can generally share the information, except for internet use. If the information is going to be placed on the internet, then special rules apply according to EU regulation. In this case, the EU directives conflict with the Swedish law so a compromise had to be made. The new laws state that if a record is over 100 years old, then it is completely open for use, but what about the time period between 70 and 100 years? The Swedish National Archive was given the responsibility to set appropriate guidelines.

The episode ends with a short interview with Thord an Kathrine to offer suggestions for people doing their genealogy.

What do we learn for Swedish genealogy?

- The police records of registration (List A, and B) that were discussed in this article can be found in Nationell Arkivdatabas under: Göteborgs Poliskammare arkiv, DXIVa, Journaler över prostituerade

- The medical clinic records that were discussed in this article can be found in Nationell Arkivdatabas under: Göteborgs Poliskammare arkiv, DXIVb, Diverse journaler, liggare m.m. angående prostituerade (for Besiktningsjournal)

- The cities that required the registration of prostitution were Stockholm, Göteborg, and Malmö.

- If you are starting your research, begin by going to living relatives to gather the family knowledge

- Verify the family knowledge in records (some information might have been remembered wrong)

- Too often people try to jump to an early generation (which is difficult), start with information that you know. Build from the known to the unknown.

- Check with other more experienced researchers. They can offer tips and guidance to help you progress faster.

- Many people believe that most genealogical information can be found in databases. Although there are many great databases to help, you cannot complete your genealogy by databases alone.

- The privacy laws for records in Sweden state that records over 100 years old are open to the public. Records that are younger than 70 years old, must be evaluated for sensitive information.

Kriminalpolisen i Malmö DIV:1 (1877) Bild 64 / sid 61

Used by permission from Arkiv Digital at http://www.arkivdigital.net/

Kriminalpolisen i Malmö DIV:1 (1877) Bild 64 / sid 61

Source:

Program: Släktband by Gunilla Nordlund and Elisabeth Renström

Season: 1 – Genealogy Courses and Other Useful Topics

Episode: 2 Kvinnorna i prostitutionsarkiven

Date of publication: 14 November, 2004

Published by: Sveriges Radio P1

Language: Swedish

Link to episode: Släktband 1:2 Kvinnorna i prostitutionarkiven